The Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA) is recognized around the world as the most important wildlife conservation law ever passed.

The History of the Endangered Species Act

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA) is a multifaceted law with a complex history. It was part of a wave of environmental legislation known as the Green Revolution, initially inspired by Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring, a nationwide, grassroots movement that drew further inspiration from headline-making catastrophes such as the Santa Barbara oil spill and the Cuyahoga River fire, both in 1969, and its tactics from the civil rights movement and the mass protests against the Vietnam War. Altogether, sixty-seven environmental and consumer protection laws were enacted by Congress in the 1960s and ’70s. Subsequent crises such as the Love Canal and Three Mile Island disasters provided continued momentum.

Throughout this period, Congress responded to the public demand for action, often with complex regulatory schemes such as the National Environmental Policy Act (1970), the Clean Air Act (1970), the Clean Water Act (1972), the Endangered Species Act (1973), and the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), also known as Superfund (1980). The ESA, however, is an outlier among these. While all of these laws created new federal regulatory systems, the ESA was unique in that it was also grafted onto a centuries-old tradition of wildlife utilization by the American people, and wildlife management by state and local authorities. The result was a law more far-reaching than many realized, more difficult to implement and administer than expected, and more controversial than its contemporaries.

Throughout its history, the ESA has been shaped by three concurrent sources of law: legislative amendments, administrative rules (and related policies), and judicial opinions. The drama of the ESA has further played out in the realms of politics, media attention, and public opinion. The following paragraphs briefly describe this history – a more complete history and analysis can be found in The Codex of the Endangered Species Act, Volume I: The First Fifty Years.

Ivory-billed woodpecker skins. ©Joel Sartore/Photo Ark.

Before the Endangered Species Act

In the earliest days of the American colonies, wildlife was an unregulated natural resource freely available for the taking, and an important source of food and raw materials. As the colonies grew, gained their independence from Great Britain, and became the United States, human pressure on wildlife populations mounted. Species such as buffalo, deer, and countless birds were slaughtered en masse, providing food, hides, fur, decorative feathers, and sport.

In the late 19th Century, growing awareness of this slaughter – and an emerging awareness of the possibility of species extinction due to human action – gave birth to the conservation movement. Initially made up of hunters, anglers, writers, and naturalists, the movement began among sporting and fishing clubs, and organizations such as the Smithsonian Institution and the New York Zoological Society. Leading lights such as George Perkins Marsh (1801-1882) and Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) wrote eloquently of the natural world and sounded the alarm at its loss. Species lost in this period and thereafter included American icons such as the passenger pigeon, heath hen, Carolina parakeet, great auk, Labrador duck, and the “Lord God Bird” – the ivory-billed woodpecker.

These early conservationists inspired the next generation of leaders, which included such figures as George Bird Grinnell (1849-1938), William T. Hornaday (1854-1937), Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), and Gifford Pinchot (1865-1946), who led movements to save species such as buffalo, deer, and elk. Roosevelt, Grinnell, and Pinchot, among others, further led the U.S. government in establishing protected reserves for wildlife and forests. The creation of formal government structures around conservation led to demand and funding for a new, professional approach to wildlife management, the development of which was largely inspired by the work of Aldo Leopold (1887-1948). The advent of formal training in biology, ecology, zoology, and other wildlife sciences produced a professional corps of scientists and leaders who also went to work for state fish and wildlife agencies, which had exercised jurisdiction over fish and wildlife as public trust resources since the earliest days of the Republic. By the post-World War II period, America enjoyed a mature, robust system of wildlife management known as the “North American Model,” yet species declines and extinctions continued.

The Endangered Species Acts of 1966 and 1969

A large part of the development of wildlife conservation throughout the early 20th Century was the gradual expansion of federal authority into the realm of wildlife management, including through the Lacey Act (1900), Migratory Bird Treaty Act (1918), Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act (Pittman-Robertson Act, 1937), Bald Eagle Protection Act (1940), Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Act (Dingell-Johnson Act, 1950), and Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act (1962).

Events in the 1960s then galvanized America and its leaders in Congress to act. Foremost among these was the publication in 1962 of Rachel Carson’s legendary Silent Spring, documenting the deleterious impact of pesticides on bird reproduction. The Endangered Species Act that we know today was preceded by two more limited versions passed in 1966 and 1969, respectively. The process was actually initiated by the U.S. Department of the Interior, which convened a Committee on Rare and Endangered Wildlife Species which published a report in 1966, prompting the department to seek authority for the federal government to conserve endangered species under existing programs such as the 1956 Fish and Wildlife Act, the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act of 1934, the Land and Water Conservation Fund of 1965, and the Migratory Bird Conservation Act of 1929.

Congress responded with the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966, which authorized the use of public lands and federal resources for protected habitat, sanctuaries, and propagation of select species. However, the contents of the proposed programs were basically unspecified, and the law proved ineffective with little real authority or prohibitions to prevent the killing or interstate trade in endangered species, and had no authority to ban the import of foreign endangered species or parts thereof.

Just four months later, Congress began considering amendments to the new law. This legislation, which ultimately became the Endangered Species Conservation Act of 1969, focused on limiting the importation of endangered species and products derived from endangered species. These goals were partially achieved, but the effectiveness of the legislation was limited by a generous hardship exemption for those engaged in trade of endangered species, a lack of restrictions on domestic trade or “take” of listed species, no mechanism for habitat protection, and a failure to include plants or most invertebrates. The legislation also directed the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of State to convene an international ministerial meeting on fish and wildlife in order to develop a binding international convention on the conservation of endangered species, which ultimately led to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

Enacting the Endangered Species Act

In the early 1970s, the impetus for an expanded, improved ESA primarily came not from Congress or the public but from the Nixon administration. President Nixon had seen the energy of the new environmental movement on display at the first Earth Day, April 22, 1970. Nixon wanted to capture the support of this visible and vocal voter block. He directed his domestic policy advisors John Ehrlichman and John Whitaker to pursue and support the creation of environmental laws such as the Endangered Species Act, regardless of which political party originated them, since both houses of Congress were controlled by the Democratic Party.

Operation Breathe Free motorcade, 1967. Library of Congress.

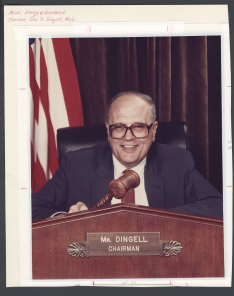

Representative John D. Dingell, Jr., Chairman of the Subcommittee on Fisheries and Wildlife Conservation and the Environment. Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives.

In 1971, Representative John D. Dingell (D-MI), who had sponsored the 1969 act, introduced legislation to expand its purview to include threatened species under the ESA. The Nixon administration simultaneously began drafting entirely new endangered species act to supersede the 1966 and 1969 acts. The Nixon administration’s version of the new ESA was initially drafted at the Interior Department by a working group consisting of Nathaniel P. Reed, Assistant Secretary for Fish, Wildlife and Parks, his Deputy Assistant Secretary E. U. Curtis “Buff” Bohlen, and Douglas Wheeler, also a Deputy Assistant Secretary to Reed. From the White House CEQ Chairman Russell Train, and Dr. Lee Talbot were intensely involved in consultation, but more in the conceptualization of the bill. At Interior, Reed, Bohlen, and Wheeler were occasionally joined by Earl Baysinger, Acting Director of the FWS Office of Endangered Species, Clark Bavin, Chief of the FWS’s law enforcement division, and Cleo Layton, a member of Reed’s senior staff, who all worked collaboratively as a team. In the Congress, the effort was led by Representative Dingell, with whose staff the “Train Team” closely coordinated.

The CITES conference in Washington, March 1973. Photograph by the U.S. Department of State, 1973.

On February 8, 1972 President Nixon announced “legislation to provide for early identification and protection of endangered species” that “would make the taking of endangered species a Federal offense for the first time, and would permit protective measures to be undertaken before a species is so depleted that regeneration is difficult or impossible.” Throughout 1972, Congress through its committee process and the administration refined and expanded the concept into legislation that closely approximated the ESA that would become law the next year.

In every aspect, the new legislation was more detailed, complete, and unyielding than the 1966 and 1969 acts. Compulsory language – “shall” – defined numerous aspects of the law, including its binding requirements for compliance by federal government agencies. A carefully prescribed listing process was included, entirely under federal authority. “Threatened” as well as “endangered” species could be protected. Not only import and export but taking, possession, sale, delivery, and transport of listed species were all prohibited. Expanded funding provisions allowed for acquisition of habitat and funding of state conservation programs for endangered species. Strict civil and criminal penalties were provided for violations of the act, with exceptions only “for scientific purposes or to enhance the propagation or survival of the affected species,” or a limited “hardship exemption.”

The ESA represented a revolutionary expansion of federal power over wildlife, but it was firmly rooted in the U.S. Constitution. Earlier wildlife laws such as the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 were based on the Treaty Clause of the Constitution, and the ESA followed in this tradition by invoking six specific international treaties, and by being the means of implementation for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which was signed in Washington on March 3, 1973.

Most of all, courts have found that the ESA is a valid exercise of the Commerce Clause, which grants Congress the power to regulate interstate commerce. This applies even to cases of intrastate species or de minimis impacts, because the ESA is a “comprehensive regulatory scheme” that explicitly preempts state authority over listed species, and, as the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals held in a 2017 case, Congress rationally concluded that “protection of purely intrastate species is essential to the ESA's comprehensive regulatory scheme.”

Nixon signed the ESA into law on December 28, 1973, saying: “Nothing is more priceless and more worthy of preservation than the rich array of animal life with which our country has been blessed. It is a many-faceted treasure, of value to scholars, scientists, and nature lovers alike, and it forms a vital part of the heritage we all share as Americans.”

The snail darter. ©Joel Sartore.

Controversial Beginnings and the Snail Darter Case

Although the U.S. Department of the Interior moved swiftly to reconcile the existing list of endangered species (listed under the 1966 act) and protect those species under the new ESA, the process of developing implementing regulations and procedures for the new law was protracted. The core regulations that provided for listing species and protecting them from take were implemented in 1975, as was funding for state programs under Section 6, and implementation of Section 7 consultation among federal agencies followed in 1978. One significant aspect of the initial implementation of the law was that the Section 6 regulations provided only for funding of state conservation programs for threatened and endangered species, and afforded states no role whatsoever in administration of the ESA itself, nor any voice in management of species under the ESA. This was a departure from the language and expectations of Congress during the development of the law, but was tacitly accepted thereafter and remains the practice to this day.

When Congress was debating the ESA in 1971-1973, archival records show that America’s focus was on iconic charismatic species such as the bald eagle, whooping crane, alligator, whales, etc. But the law that was passed afforded equal protections to the least charismatic species as well – something that both the administration and Congressman Dingell well understood. It was a surprise to most, however, when the ESA’s first high-profile controversy centered on the lowest profile of species: the snail darter, a tiny fish that was thought to live only in the Little Tennessee River.

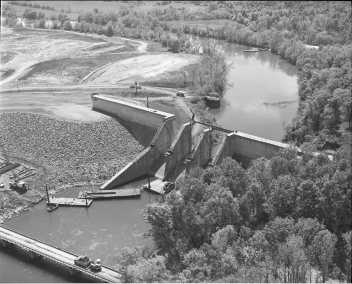

Tellico Dam under construction. Courtesy of the Tennessee Valley Authority.

The controversy that ultimately led to the U.S. Supreme Court case Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill was a long, hard-fought battle over the Tennessee Valley Authority’s (TVA) plan to build the Tellico Dam on the Little Tennessee River. First planned in 1959, Tellico ostensibly was intended to divert water a short distance upstream to the reservoir above the Fort Loudon Dam on the main stem of the Tennessee River, increasing the power of the hydroelectric plant at that location. But the TVA condemned not only the 16,500 acres that would be inundated by the new reservoir but a total of 42,999 acres of private land to create housing projects, a model town, and industrial parks around the new lake, at the cost of private homes, sacred native American burial sites, and some of the finest trout-fishing waters in the United States.

The battle over the Tellico Dam predated the ESA, but in 1973 University of Tennessee ichthyologist Dr. David Etnies discovered the snail darter. Due to the efforts of University of Tennessee law student Hiram Hill and his professor Zygmunt J.B. Plater, the snail darter was listed as an endangered species under the ESA in 1975. In 1976, a federal district court held that the Tellico Dam would “adversely modify” and perhaps destroy the snail darter’s critical habitat, in violation of Section 7 of the ESA. However, the court allowed dam construction to continue because it was already under way. In fact, the $116 million dam was already over 90% completed. However, in 1977 the U.S. Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the district court and ordered construction halted, a decision that was upheld by the Supreme Court on June 15, 1978.

Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill struck the ESA like a thunderbolt. Members of Congress, led by Tennessee Representative John Duncan, Sr. and Tennessee Senator Howard Baker, Jr., were enraged. They engineered a massive expansion to Section 7, the part of the ESA that prohibited federal agencies from actions that would jeopardize the existence of listed species or adversely modify their critical habitat. In 1978, Congress established the Endangered Species Committee, also known as the “God Committee” or “God Squad,” a complex, unwieldy system that could theoretically exempt a project from the ESA, and even allow a species to go extinct. The God Squad considered such an exemption for the Tellico Dam but unanimously refused to do so. Thereafter Duncan and Baker made numerous attempts to compel the completion of the dam, finally succeeding in 1979 through a rider on the Energy and Water Development Appropriations Act for 1980, and the dam was completed on November 29, 1979, extirpating the snail darter population in the Little Tennessee River. The snail darter survived in other nearby streams, however, and was downlisted to threatened in 1984 and delisted in 2022.

The impact of the snail darter case would reverberate through the ESA ever after. In TVA v. Hill, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger wrote that the “plain intent of Congress in enacting this statute [the ESA] was to halt and reverse the trend toward species extinction, whatever the cost” [emphasis added]. To this day, the ESA is seen as an absolute mandate to conserve wildlife and its habitats, and therefore as an impediment to construction and other human activities. Addressing this tension is one of the major challenges for the future relevance and effectiveness of the ESA.

Further Legislative Amendments and Improvements

Throughout the late 1970s and 1980s, Congress was busy conducting regular oversight of the ESA and implementing a series of amendments and improvements. The Tellico Dam controversy actually arose during one of these periodic amendments, affording the opportunity for the implementation of the “God Squad” discussed above. Other significant amendments were also made in 1978, including new provisions governing the process for listing species, the definition and designation of critical habitat, development of recovery plans, and protection of both plants and distinct population segments of vertebrates.

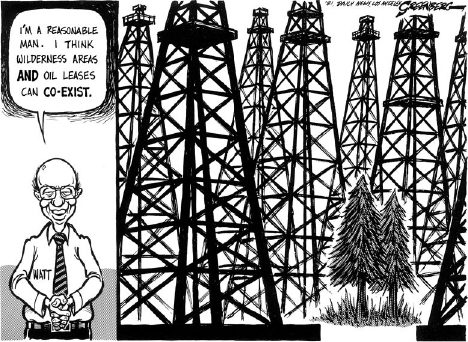

A second major amendment followed in 1982. In that year, Congress reacted to the Reagan administration’s anti-environmental policies and appointees, especially Secretary of the Interior James G. Watt, by imposing strict statutory deadlines on the consideration of ESA listing petitions. These deadlines remain part of the ESA to this day and are judicially enforceable against the government through citizen suits, which Congress expanded to be available against the government as well as against ESA violators.

1981 political cartoon by Steve Greenberg.

Congress also explicitly stated that listing and delisting must be carried out “solely on the basis of the best scientific and commercial data available,” excused designation of critical habitat if it was indeterminable, expanded the scope of Section 7 consultations, and expanded protections for plants, all in 1982.

Finally, Congress established two entirely new provisions, each of which would have far-reaching effects. First, it allowed the establishment of “experimental populations,” allowing regulatory flexibility for management of introduced populations outside a species’ current range. Second, it established “incidental take permits” for commercial or other activities that cause take of species, provided that the incidental take was consistent with an approved “habitat conservation plan” (HCP), also provided for in the 1982 amendment.

San Bruno Mountain with San Francisco in the background. Courtesy of the County of San Mateo Parks Department.

In enacting both of these new provisions, Congress sought to establish opportunities for new approaches to conservation of listed species, and these tools would later play prominent roles in the ESA, its conflicts, and successes. The very first uses of these tools illustrated Congress’ intent. The first HCP, approved in 1983, allowed a development project on San Bruno Mountain outside San Francisco, California – in fact the San Bruno Mountain Habitat Conservation Plan was the inspiration and model for the amendment. The first species to benefit from an experimental population was the Delmarva fox squirrel, under a rule established in 1984. The squirrel was successful recovered due to partnerships with state governments of Maryland, Delaware, and Virginia, and was delisted in 2015.

The final major substantive amendment to the ESA came in 1988, when Congress expanded the specific statutory requirements of recovery plans, provided for federal post-delisting monitoring of species, again made minor changes to protections for plants, and mandated annual reports to Congress on ESA expenditures. And with that, the ESA as we know it today was complete. No further legislation would follow except for riders in spending and defense bills that made minor (and usually temporary) changes to individual species or programs. What remained was the continued implementation of the law, its interpretation by courts, and the conservation programs that it would enable.

State Governments and the Endangered Species Act

In the early years of the ESA, when Congress was still providing regular oversight and amendments to the law, one of the most important questions was the role state governments would play in conserving threatened and endangered species. Going back to the beginning of the Republic following the American Revolution, state governments had exercised sovereign authority over wildlife resources, managing them as a public trust on behalf of all citizens. Only in the 20th Century did the federal government begin to have a role in wildlife management, and the ESA marked a major departure from earlier conservation laws as it mandated an exclusively federal program.

But Congress left room for state involvement as well. In pre-enactment hearings and debate on the ESA, numerous witnesses and Members of Congress appeared to suggest that states would play an equal, cooperative role with the federal government. But as enacted and applied, states were limited to a supporting role in endangered species conservation, bolstered by varying, but generally small, grants. States retained all of their traditional authority and wildlife management tools for non-listed species in parallel with the new federal program, and whether state and federal authorities are able to cooperate on endangered species recovery often depends on the relationships and goodwill that exists between the leaders involved. Such cooperation has been essential to numerous conservation successes.

Moose Henderson/iStock by Getty Images.

The Delmarva Fox Squirrel

The Delmarva fox squirrel is a large tree squirrel that was listed under the ESA’s precursor act in 1967. Historically threatened by hunting, the listing of the species ended that threat, but did nothing to address the significant contraction of the species’ population and range. Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service thereafter collaborated on a decades-long campaign of public education, habitat preservation, and translocations across fragmented habitat to establish new populations, ultimately leading to the successful recovery and, in 2015, delisting of the species.

Jean Beaufort/www.publicdomainpictures.net.

The Grizzly Bear

The iconic North American grizzly bear, one of the most recognizable and charismatic of all megafauna, was listed as a threatened species in 1975. The population was divided into five different Distinct Population Segments, and a recovery plan prepared in 1982. Immediately thereafter, management of the species took a unique turn. In 1983 the U.S. Forest Service, the National Park Service, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Geological Survey, and representatives of the state wildlife agencies of Idaho, Montana, Washington, and Wyoming came together to form the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee (IGBC) and assume joint responsibility for implementing the recovery plan in a unique federal-state partnership.

Subcommittees of technical experts were appointed to oversee the management of each recovery area, and by 2007 the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem Distinct Population Segment in and around Yellowstone National Park was ready for delisting. A long series of lawsuits have prevented the realization of the delisting that the population richly deserves, but that should in no way detract from the accomplishment of the state and federal partners in conserving this species.

Another grizzly population, the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem Distinct Population Segment, is almost ready for delisting as well, and managers foresee a time in the not-too-distant future when wide-ranging bears will begin to cross between the two populations. This connectivity, in turn, will only be possible with the cooperation and partnership of private landowners, who are already working through grassroots organizations such as the Blackfoot Challenge to conserve grizzlies and reduce human-bear conflicts. In the case of the grizzly bear, one successful collaboration is inspiring others, and all are bearing fruit in the form of the recovery of this legendary American species.

Jean Beaufort/www.publicdomainpictures.net.

The Black-Footed Ferret

The black-footed ferret, like the Delmarva fox squirrel, was listed in 1967, a victim of the relentless extermination of prairie dogs – the ferret’s sole source of food – as pests throughout the settlement of the great plains. The black-footed ferret was actually thought to be extinct as early as the 1950s, but in 1964 a small population was discovered in Mellette County, South Dakota. Nine individuals from this population were taken into captivity for the first attempt at a captive breeding program. Unfortunately, breeding was unsuccessful and the wild population died out in 1974 with the captive population following in 1979.

The ferret was then thought to be extinct until its rediscovery on the Hogg ranch near Meeteetse, Wyoming on September 26, 1981. The Meeteetse population instantly became one of the most studied and most photographer wildlife populations in America, until 1985 when it crashed due to canine distemper and plague. Wyoming Game and Fish Department officials, aided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, a team of nongovernmental volunteer scientists, and numerous zoos raced to take the entire surviving population into captivity and initiated a second, successful captive breeding program.

From an initial population of 18, the captive breeding program has now produced over 10,000 ferrets, with no ill effects from inbreeding. Captive-bred ferrets have been released at over 30 locations, including both public and private lands, and they (and associated prairie dog towns) are protected by a variety of collaborative mechanisms including experimental populations (authorized by Congress in 1982) and safe harbor agreements (created by regulation in the late 1990s), intensively managed to prevent the spread of plague. Full recovery and delisting of the species is now clearly achievable, provided that time, funding, and the collective will can be found to continue the captive breeding and reintroduction program at a sufficient scale.

Black-footed ferret release outside Meeteetse, Wyoming, 2017. Kimberly Fraser/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

John and Karen Hollingsworth/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Digital Library.

The Northern Spotted Owl

The snail darter may have been the first controversial ESA-listed species back in the 1970s, but in the 1980s it was overshadowed by what would become the most acrimonious and controversial species ever protected by the ESA: the northern spotted owl.

The northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina) is a large owl that exclusively inhabits old-growth forests from northern California up into British Columbia, and is a proxy for old-growth within its range. Throughout the 20th Century, right up to 1988, U.S. National Forest timber production steadily increased or else remained level, as old-growth forests fell to provide a growing nation and world with timber for construction and wood products. In the late 1970s and 1980s, environmentalists increasingly spoke out against this, leading to a wide-ranging political, legal, and moral controversy that became known as the Timber Wars.

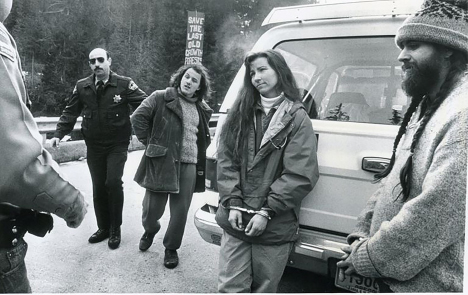

Protesters arrested at the “Easter Massacre” in Willamette National Forest, 1989. Gerry Lewin/USA Today Network.

The owl was actually a factor in the Timber Wars as early as 1978, when the Portland Audubon Society administratively challenged the Forest Service’s 1977 Spotted Owl Management Plan in the Northwest. Throughout the 1980s, environmental litigants argued that in its timber sales, the Forest Service was ignoring its own management directives to preserve biodiversity through the use of “management indicator species” such as the northern spotted owl.

What began as a controversy over management of National Forests became a controversy over the Endangered Species Act in 1990, when the owl was listed as a threatened species. Public attention, and increasing bitterness, focused on the owl.

The media, looking for simplistic, recognizable 30-60 second sound bites that would resonate with the public, loved the spotted owl narrative. What could have been a complex policy debate about natural resource values, government agency priorities, and environmental externalities weighed against corporate profit motives, instead devolved into a bitter, acrimonious debate about owls vs. jobs and timber-dependent families and communities.

Meanwhile, the George H. W. Bush administration engaged in a series of unsuccessful attempts to thread the needle between scientific necessity and political expediency. A series of scientific panels were convened and issued reports, including the Interagency Spotted Owl Committee in 1990 and the “Gang of Four” in 1991. These were unanimous in their conclusions that existing levels of harvest on Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) forests were incompatible with the survival of the owl. Under Director Cy Jamison, BLM first tried to ignore these reports, then invoked the “God Squad” (of snail darter fame) and sought to exempt its timber sales from the ESA, even if that led to the extinction of the owl. The God Squad granted 13 of 44 requested exemptions, but its action was overturned by a federal appeals court.

The President’s Northwest Forest Summit, 1993. Bureau of Land Management/Flickr.

The owl controversy spilled over into the 1992 presidential election campaign, and Democratic candidate Bill Clinton promised to convene a top-level summit to address the issue, which led to the President’s Northwest Forest Summit in Portland, Oregon on Friday, April 2, 1993. Thereafter, the Clinton administration developed the Northwest Forest Plan, which was adopted in 1994 and governs management of public lands in the Pacific Northwest to this day.

Unfortunately, the northern spotted owl has continued to decline, primarily due to competition from the larger, invasive barred owl. Its eventual extinction is a very real possibility. And it has become the poster child for opposition to the ESA. Whenever a local community is concerned about a potential listing having detrimental economic effects, the owl is invoked and there is fear that that species will be “the next spotted owl.”

The spotted owl saga unfolded at a time when our politics were becoming radicalized, a process that began in the 1990s and has since only accelerated, and become a dangerous cancer gnawing at the heart of American democracy. As evidenced by the northern spotted owl, the Endangered Species Act played a significant role in that politicization of environmental protection. What comes next for America may depend, in part, on whether the ESA can now be used to depoliticize environmental protection, by finding win-win solutions that benefit species and humans alike. The seeds of that, too, were sown in the chaotic 1990s, in regulatory flexibilities and collaborative conservation efforts.

Legislative Gridlock

The northern spotted owl directly contributed to what has since become a permanent breakdown in the regular, orderly oversight and implementation of the Endangered Species Act. From the earliest days of the ESA in the 1970s right through the 1988 amendments to the ESA, Congress closely monitored the condition of species and the implementation of the ESA, regularly reauthorizing it and making both major amendments (in 1978, 1982, and 1988) and a series of minor amendments to address issues and conflicts as they arose.

After 1988, this ended. The ESA was due to be reauthorized again in 1992, as it had been several times in the past, but reauthorization bills introduced by both Democrats and Republicans were tabled by Democratic leadership in Congress, who were facing strong political headwinds in a presidential election year. They no doubt assumed that they would take the ESA up again in a future Congress, but instead the ESA has languished without substantive amendment ever since, now for over thirty years. It is still a valid law only because it is included in annual appropriations legislation each year.

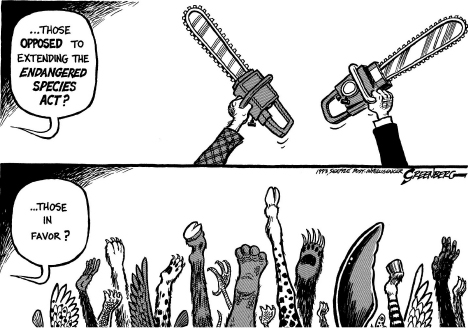

1993 political cartoon by Steve Greenberg.

Why did this happen? First, the spotted owl made the ESA politically toxic, and etched in America’s collective consciousness the false premise that species could not be conserved without costing jobs. Second, the seeds of the Republican Revolution of 1994 were planted in the 1992 elections, with a new class of uncompromising, conservative Republicans elected. These members of Congress were aligned with the Wise Use Movement, the County Movement, and calls for increased private property rights, and viewed the ESA as the antithesis of everything that they stood for. When the Republican party seized control of both the House and Senate in the 1994 elections, they became ascendant. Congress in the later 1990s not only failed to update and amend the ESA, it also shut down the federal government for 21 days in 1995-1996 and imposed a year-long moratorium on listing species under the ESA from April 1995 until April 1996. Thereafter, the ESA remained a political football in the partisan politics of Capitol Hill.

Today the ESA has become a third rail in American politics, a topic too dangerous for either Republican or Democratic officials to address in meaningful dialogue. Instead, we are left with political posturing and gross caricatures, where one side claims that the ESA is an infallible success that should never be amended, while the other sees is as an abject failure and impediment to economic prosperity that must be heavily amended, if not abolished. Neither perspective is historically accurate nor tenable, yet both persist.

Regulatory Flexibilities

One way we might begin to move beyond legislative gridlock is through the use of regulatory flexibilities available in the ESA. The Clinton administration, led by Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt, developed a series of three innovative regulatory flexibilities within the existing ESA, and then used them to work around the legislative gridlock in Congress. In the decades since, these flexibilities have only grown more popular. In the future, we can not only continue their use, we can also use their success to identify opportunities for legislative amendments to enable more flexibilities within the ESA, and more win-win compromises for humans and wildlife alike.

The first new regulatory flexibility was “No Surprises” for Habitat Conservation Plans. As created by Congress in 1982, HCPs were difficult to develop. But as of the end of 1992, just 14 HCPs had ever been developed, including the original San Bruno Mountain HCP. Secretary Babbitt saw HCPs as a potential solution to the problem of northern spotted owl management on private properties, but the experience of timber companies was that they were an expensive slippery slope – no sooner would an HCP be completed than new science would emerge and the entire process would have to be started over.

To address this, the administration developed a regulation providing for “No Surprises,” which stated that “no additional land use restrictions or financial compensation” would be required of an incidental take permitholder, “even if unforeseen circumstances arise after the permit is issued indicating that additional mitigation is needed.” In other words, if a private landowner went through the lengthy process of developing a HCP and securing an incidental take permit, they could be confident that nothing more would be required of them for the species covered by the HCP. This innovation made the HCP a viable conservation tool, as it remains to this day. Thanks to No Surprises, today there are over 1,000 HCPs encompassing over 48 million acres.

The second new regulatory flexibility was Safe Harbor Agreements (SHAs). This arose due to the issue of red-cockaded woodpeckers on and around Fort Bragg, North Carolina, which in the early 1990s began to interfere with the ability of the U.S. Army to carry out training and other operations at the fort. Beginning in 1992, the Department of the Defense, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Environmental Defense Fund began work on a specialized habitat conservation plan. Their concept was that if a landowner voluntarily managed their land to increase red-cockaded woodpecker habitat, they would be protected from any liability under the ESA should they later reverse their approach and reduce the red-cockaded woodpecker habitat on their property. The only limit was they could not reduce it below the “baseline” set when they enrolled in the program. The Clinton administration embraced this initiative, and further developed it into the SHA concept, applicable to any listed species, which was finalized in 1999. Today, there are over 100 SHAs in effect across the country, covering dozens of species and millions of acres of land.

The final new regulatory flexibility was Candidate Conservation Agreements with Assurances (CCAAs). Safe Harbor Agreements were designed to entice private landowners to conserve threatened and endangered species. Candidate Conservation Agreements with Assurances, which were developed in tandem with SHAs, extended this concept to candidate species that were not yet listed. Under a CCAA, a landowner agrees to implement conservation measures to benefit one or more candidate species. In exchange, they receive assurances that additional conservation measures above what they have agreed to will not be required, even if the species becomes listed, and that they may continue existing and agreed-upon land uses that have the potential to cause incidental take, provided that they were agreed upon in the CCAA. Since 1999, more than 40 CCAAs have been developed or proposed.

The development of these tools, and their embrace by private landowners and other regulated entities, proves that the ESA is not the insurmountable obstacle to prosperity that its opponents have claimed it to be. But there is much work yet to be done.

Collaborative Conservation

The central purpose of the Endangered Species Act is to conserve species. Its central tension is the great, unresolved question of how? With No Surprises, Safe Harbor Agreements, and Candidate Conservation Agreements with Assurances, the Clinton administration pioneered opportunities for landowners to work with the ESA. They came at a time when others were independently beginning to seek creative, conflict-reducing opportunities for wildlife conservation.

Collaborative conservation, as defined by Executive Order 13,352, issued by George W. Bush in 2004, encompasses “actions that relate to use, enhancement, and enjoyment of natural resources, protection of the environment, or both, and that involve collaborative activity among Federal, State, local, and tribal governments, private for-profit and nonprofit institutions, other nongovernmental entities and individuals.”

Collaborative conservation has a long history in America, dating back over 100 years to when conservationists such as Theodore Roosevelt, George Bird Grinnell, and William Temple Hornaday led successful campaigns to preserve species such as bison, elk, antelope, white-tailed deer, and colorful waterfowl of all sorts. Modern collaborative conservation builds on this legacy, but operates in the framework of widespread species endangerment, degradation of air and water quality, and biodiversity loss. In light of the many challenges that face us, effective collaborative conservation is more essential than ever before.

Collaborative conservation utilizes a diverse toolbox of regulatory, financial, and technical tools to deliver conservation on the ground. These include conservation easements, ESA assurances such as SHAs and CCAAs, federal Farm Bill programs, state and national tax benefits, grants both public and private, in-kind contributions, and more. A thorough discussion of the many programs available to private landowners can be found in Saving Species on Private Lands: Unlocking Incentives to Conserve Species and Their Habitats by Lowell E. Baier [link].

There are myriad examples of successful collaborative conservation programs. Some that involved ESA-listed species can be found on the success stories page [link]. Two examples of early collaboratives show how a group may come together around a specific resource issue but then expand their focus to encompass other issues, including endangered species.

One of the best-known examples of collaborative conservation arose in the Malpai borderlands of southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico. In the early 1990s, local landowners were frustrated by excessive fire-prevention practices of state and local authorities, and they came together to develop a comprehensive landscape-scale fire plan for the entire region, and created the Malpai Borderlands Group, an ongoing grassroots organization that developed and operated (between 1996-2004) the first “grassbank” in the United States, and to this day produces and shares science-based approaches to range management.

Gray wolf. Gary Kramer/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Digital Library.

Another example is the Blackfoot Challenge, a group of landowners in the Blackfoot River Valley of Montana (the setting for A River Runs Through It). They came together in the 1970s to restore the Blackfoot River, which was one of the most imperiled rivers in the country due to pollution from mining tailings, timber harvest, and grazing practices. The landowners came together to discuss ways to protect their river and their agricultural way of life, and eventually formed the Blackfoot Challenge, a non-profit that works to this day with landowners, leaders, and partners among private, local, state, and federal organizations in order to achieve on-the-ground conservation objectives. The organization works with local landowners, state and federal agencies, and other nonprofits such as Defenders of Wildlife and The Nature Conservancy to manage livestock in ways that are reducing mortality from depredation by listed grizzly bears and gray wolves.

Louisiana black bear cubs with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Regional Director Cindy Dohner. Courtesy of Cindy Dohner.

One of the most exciting collaborative conservation efforts today is Conservation without Conflict, a new initiative thirty years in the making. In the early 1990s, in the midst of the northern spotted owl controversy, the Louisiana black bear was listed as a threatened species. In the fact of dire expectations that the species would be “the next spotted owl” or “the spotted owl of the south,” the local forestry industry took decisive action. Engaging state wildlife agencies, landowners, federal scientists, and national experts, the Louisiana Forestry Association hosted a series of meetings that culminated in establishment of the Black Bear Conservation Committee (later the Black Bear Conservation Coalition), which helped develop a recovery plan and manage the species to a successful recovery and delisting in 2016.

Because of this program, and other efforts on behalf of the gopher tortoise, black pinesnake, Louisiana pinesnake, longleaf pine, and other species, the American south has a long tradition of successful, collaborative conservation. On April 20, 2010, the Tucson, Arizona-based Center for Biological Diversity filed the second-largest single ESA petition ever, seeking the listing of 404 aquatic, riparian, and wetland species in the Southeast (the largest petition ever covered 475 species, filed by Forest Guardians – now WildEarth Guardians – in 2007). In response, the fifteen states in the Southeast and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region worked together to develop the Southeast Conservation Adaptation Strategy to keep as many of those petitioned species as possible off the lists of threatened and endangered species.

This started a snowball effect of ever-growing conservation partnerships. The National Alliance of Forest Owners (NAFO), which represents landowners that own and manage a total of 46 million acres of forests across the United States, established the NAFO Wildlife Conservation Initiative to partner with government agencies and supports its members as they worked to finance, establish, and maintain young forest, open canopy forests, and healthy riparian and aquatic habitats to benefit wildlife even while managing their lands as working forests to achieve both economic and environmental ownership objectives.

By 2021, collaborative efforts in the Southeast had resulted in 205 species not needing to be listed under the ESA, through a combination of negative 90-day findings on petitions, not warranted 12-month listing determinations, and listing petitions being withdrawn. This success has led to an even-larger group of regional and national leaders to establish a nationwide coalition to promote the idea that voluntary proactive collaborative conservation that recognizes the importance of working farms, ranches, and forests can achieve greater conservation success than mandated regulatory approaches. This is now both an approach to wildlife conservation and a national coalition known as “Conservation without Conflict,” which hired its first staff in 2021 and hosts a growing number of events and resources to promote collaborative conservation across America.

Endangered Species Litigation

The evolution of the Endangered Species Act over the last 50 years cannot be understood without the increasingly prominent role of courts and litigation. The 1990s sowed the seeds of both legislative gridlock and innovative collaborative conservation efforts. They also saw the beginning of an ongoing, growing trend of environmental groups using litigation to direct the ESA program and the government’s listing priorities. In 1992, President George H.W. Bush imposed a moratorium on new regulations, including ESA listings. In response, an environmental activist named Jasper Carlton sued, arguing that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was violating the 1982 statutory deadlines for listing species. Rather than permit the court to rule and potentially order immediate action on 401 species that were then candidates for listing, the government agreed to a negotiated settlement, under which it would resolve the conservation status of the 401 candidate species by September 30, 1996, by either listing them or determining they no longer warranted listing.

In the 2000s, this would become a model for environmental groups to use to influence the ESA program. Throughout the decade, an increasing number of lawsuits forced the listing of more species and the designation of more critical habitat. The lawsuits followed behind what became known as “mega petitions” such as the 2007 petition for 475 species filed by Forest Guardians and the 2010 petition for 404 species filed by the Center for Biological Diversity. Other large petitions included one for 225 species in 2004 and one for 206 species in 2007. The ESA requires the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to respond to petitions within 90 days – which is impossible when several hundred species are petitioned at the same time.

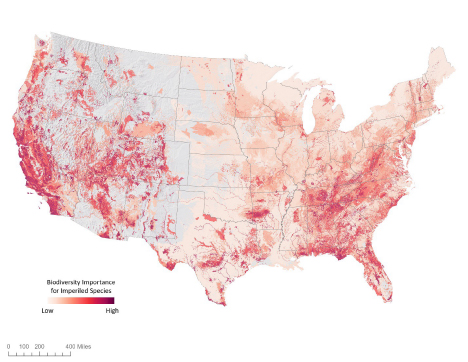

This 2022 NatureServe map models imperiled species (taking range size into consideration), illustrating the extent of the biodiversity crisis. Map copyright © 2022, NatureServe, 2550 South Clark Street, Suite 930, Arlington VA 22202, USA. All Rights Reserved.

By 2010, the Fish and Wildlife Service had had enough. It sought consolidation of 12 different cases from four district courts into a single “multidistrict litigation” in order to facilitate a settlement. The resulting agreements with the Center for Biological Diversity and Wildearth Guardians were unprecedented in scope. The government agreed not only to address the listing of the species covered by the consolidated cases, but those in several other cases, and 600 other petitioned species. Moreover, it agreed to examine all 251 species then identified as candidates for listing and either find that listing those species was warranted or not warranted, foregoing the option of maintaining them on the candidate list. Altogether, the two settlements included listing or critical habitat determinations for 1,030 species, subspecies, and populations and established 1,559 judicially enforceable deadlines between 2010 and 2017.

To fulfill the terms of these settlements, the Fish and Wildlife Service developed a listing workplan for 2011-2016, which laid out which species would receive 90-day determinations, 12-month listing determinations, and critical habitat designations in each year. The workplan was based on the FWS’s projection of its budget and capacity, and over the next several years the agency methodically worked through the actions on the workplan. The listing workplan successfully increased the orderliness and transparency of the agency’s ESA workflow, and it was subsequently updated for 2013-2018, 2017-2023, and most recently 2021-2025. In 2020, the agency followed with its first downlisting and delisting workplan, covering 2020-2023.

Together, these workplans have brought more clarity and certainty to the ESA program, greatly reducing litigation. They have not changed the fact, however, that mega petitions and subsequent listing deadline lawsuits can allow private, special interest groups to effectively take control of the ESA program’s priorities. ESA deadline lawsuits continue to be filed, and there is no protection against the government again becoming overwhelmed by them.

Ecosystem Conservation

The new trend of mega petitions and ESA deadline lawsuits has driven not only listing actions but also conservation of species. One of the lessons of successful collaborative conservation is that it takes time to establish relationships, build trust, develop a plan, and put it into action. Too often, when dealing with listed and at-risk species, conservation efforts are launched too late. One strength of the new listing workplan approach to the ESA is that it provides longer lead times for effective conservation.

The greater sage-grouse. Tom Reichner/Shutterstock.

The sagebrush ecosystem of the American West. Wayne Broussard/Shutterstock.

The Greater Sage-Grouse

The greater sage-grouse is a large grasslands bird that can be found across 11 western states (California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming). The species’ range has declined 44 percent from its historic 297 million acres. It is a sagebrush-obligate species, feeding exclusively on sagebrush in winter and relying on sagebrush for cover from predators during nesting and brood-rearing seasons. Widely recognized as the iconic species of the “sagebrush sea,” this grouse is an ecological indicator species for 353 species that share the same ecosystem, including the pygmy rabbit, pronghorn, badger, loggerhead shrike, mule deer, golden eagle, western burrowing owl, greater shorthorned lizard, and sage thrasher.

The species was first described by Meriwether Lewis in a journal entry dated May 2, 1806, and was celebrated by Dr. William T. Hornaday, who called for its protection from overhunting as early as 1916. Awareness of the sage-grouse’s decline spread, and in 1954 the Western Association of State Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA) began to study it. In 1994, alarms were sounded regarding a possible ESA listing of the greater sage-grouse, and conservation efforts grew. By 1995, every state in the sage-grouse’s range had launched a conservation program to benefit the species. It was petitioned for listing under the ESA in 2002, but languished as a candidate species until the 2011 litigation settlements set a listing determination date of 2015.

The greater sage-grouse is best known for its mating ritual. Every spring, male sage-grouse gather in broad, open spaces called leks to perform elaborate mating rituals. Population estimates are generally based on counting breeding males present on leks each spring. The population hit a low point in 2013, when surveys counted just 48,641 breeding males, a decline of 56% from 109,990 in 2007.

Between 2008 and 2015, and continuing on through the present, the sage-grouse has benefitted from an unprecedented collaborative conservation effort, the largest and most intensive wildlife conservation effort in American history. The effort actually began before 2011. WAFWA published a series of sage-grouse conservation plans in 2004 and 2006, and in 2008 joined with six federal agencies (the Bureau of Land Management, the Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Forest Service, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the Farm Service Agency) to facilitate sage-grouse conservation. Individual states and governors then helped elevate the issue of the greater sage-grouse within the national conversation. In particular Governors Matthew Mead (R-WY) and John Hickenlooper (D-CO) approached Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar and proposed a state/federal collaboration in 2011, which ultimately evolved into the of the Sage Grouse Taskforce, a multistate collaboration with the Department of the Interior to coordinate the efforts of all 11 states in the range, all four federal land management agencies, industry, local conservation organizations, and landowners.

The contributions of each of these stakeholders are too many to list here, and are continuing today. The Fish and Wildlife Service convened a study to define what successful conservation of the species would look like. The Bureau of Land Management, which manages over 50% of the species range, developed national planning guidance and a series of step-down resource management plan amendments. These resource management plans themselves became controversial, which several of them being revised (made less strict) by the Trump administration and then revised again (made more strict) by the Biden administration. The U.S. Forest Service also established sage-grouse conservation plans for its lands within the species’ range, and the Forest Service and the U.S. Geological Survey funded countless studies of the species.

Last but certainly not least, the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Sage Grouse Initiative invested over $760 million (and counting) in sage-grouse conservation, including both U.S. government appropriations and funds raised from partner organizations. Moreover, all 11 states in the species’ range developed state plans for sage-grouse conservation, using a variety of tools including legislation, executive orders, and other regulations. Altogether, over $1.5 billion has been spent on greater sage-grouse conservation to date, a staggering sum unlikely to ever be invested in another species.

That has this done for the species? Initially, at least, success. In 2015, the Fish and Wildlife Service announced that listing of the species was not warranted. However, a new analysis published in 2021 concluded that the species’ decline has continued, with the overall population dropped 13% from 2013-2019, and 37% from 2002-2019. Although individual conservation efforts have resulted in local successes, the species is continuing to lose ground range wide as the drought in the West lingers on, as does the aggressive expansion of invasive grasses and noxious weeds, such as cheatgrass, medusahead rye, white-top, leafy spurge, various thistles, and knapweed.

The future of the greater sage-grouse is inextricably linked to the future of the sagebrush biome and associated grasslands in the American west. In recent years, millions of acres of American grasslands have been converted to agriculture, leading grasslands to be declared “the most endangered ecosystem in the world.”

Despite the historic accomplishments that have already been realized, much work remains to be done for the greater sage-grouse and the grassland and sagebrush biome. On the ground, as much as 40 million acres of sagebrush are suffering serious degradation due to invasive vegetation, primarily aggressive cheatgrass expansion, and 1 million acres are being lost or severely degraded due to wildfire every year, in part attributable to the severe drought in the West, which also promotes the growth of cheatgrass.

To address these challenges in the future will require not just sustained commitment and engagement from traditional partners but more involvement from private landowners, state agricultural agencies, and conservation organizations. The greater sage-grouse conservation effort has been unprecedented in its size and scope, as well as its achievements. But it has also shown us just how severe the need can become when our natural environment and ecosystems are allowed to become so degraded, or destroyed by natural causes such as severe drought, fires, and floods.

The lesser prairie chicken, D. Longenbaugh/Shutterstock.

The Lesser Prairie Chicken

Another species that has been the subject of intensive conservation efforts with unfortunately mixed results is the lesser prairie-chicken, a candidate species since 1999. The 2011 litigation settlements set a deadline for the species’ listing determination of 2012, which did not leave enough time for state-led conservation efforts (which had begun in earnest in 2008) to be successful. The five states in the species’ range (Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas), acting through the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA) developed an innovative, two-pronged approach to habitat conservation. They combined Candidate Conservation Agreements with Assurances for the oil and gas industry with a compensatory mitigation program, known as the range-wide plan, in which companies planning to disturb chicken habitat paid fees which were then distributed to private landowners willing to protect habitat for specified terms. This novel conservation scheme functioned akin to a conservation bank, except that WAFWA, rather than the free market, set the prices for participation by both industry and landowners, and most of the land enrolled was conserved on a temporary, rather than permanent, basis. Together, these two mechanisms raised over $64 million from industry for lesser prairie chicken conservation. In addition, the Natural Resources Conservation Service invested $41.6 million in lesser prairie chicken conservation through its Lesser Prairie Chicken Initiative.

Unfortunately, after a delay the species was nonetheless listed in 2014, due in part to a population crash from approximately 34,000 in 2012 to just 18,747 in 2013 (rebounding to 22,415 in 2014). The listing was then overturned by a federal court in Texas in 2015, and management returned to the states. Unfortunately, both the WAFWA conservation plan and the species struggled thereafter. The end of the threat of the species being listed led to a virtual cessation of enrollments in conservation plans, and a number of companies reneged on existing commitments. The species was again petitioned for listing in 2016, and following a lawsuit a proposed rule listing the species was published in 2021. In 2022, the Center for Biological Diversity filed another deadline suit to force the listing to be completed, and the species was listed in late 2022. The Northern Distinct Population Segment in Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and the Texas panhandle was listed as “threatened” while the Southern Distinct Population Segment along the Texas-New Mexico border was listed as “endangered.”

Landscape Scale Conservation

The greater sage-grouse and the lesser prairie chicken have in common with each other the fact that they cannot be conserved without conserving the fundamental biological and ecological components of the ecosystems they inhabit. In this sense they are “indicator” species, like the northern spotted owl, and they are seen as proxies for their ecosystems for both observing trends over time and designing effective conservation programs. For this reason, as well as for their status as ESA candidate species, they have attracted unprecedented levels of attention and investment. At the same time, other approaches to conservation have begun to look at landscapes and ecosystems first, and individual species second.

Among the oldest examples of this approach are the migratory bird joint ventures established by the 1986 North American Waterfowl Management Plan. Joint ventures were created to provide “a means for governments and private organizations to cooperate in the planning, funding and implementation of projects to preserve or enhance waterfowl habitat.” They can be found across virtually all of North America, and they now work not just on waterfowl but on all birds and, increasingly, all aspects of ecosystems. Joint ventures have been involved in conservation of the Louisiana black bear, greater sage-grouse, monarch butterflies, and countless other iconic, wide-ranging species.

Monarch butterfly. Sari ONeal/Shutterstock.

Wildlife and ecosystems are inextricably linked, and we increasingly understand that one cannot be conserved without the other. Congress understood this in 1973, when it stated that the purpose of the ESA was to provide both “a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be conserved” and “a program for the conservation of such endangered species and threatened species.” Many effective ecosystem conservation efforts, such as those collaboratively developed by landowners in both the Malpai Borderlands and the Blackfoot Valley, are not organized around threatened or endangered species – or even individual species at all – but nonetheless benefit those species both directly and indirectly. In many cases, these efforts arise independently of the ESA, although the threat of an ESA listing may help to motivate them.

The greater sage-grouse vividly illustrates the limits of the ESA in addressing ecosystem conservation. In 2018, researchers at the University of Wyoming found that Wyoming’s conservation plans for the greater sage-grouse, which rely on core areas, protect 82% of the sage-grouse population in the state. The researchers then examined the 52 most imperiled of the 350-plus other species in the same ecosystem. They found that sage-grouse core areas protected no more than 63% of the habitat of any of those species, and in some cases 0% of their habitat, despite the sage-grouse supposedly being an indicator species for these other species.

In 2021, another study found that among 70 reptiles in the sagebrush ecosystem, 22 species have greater than 10% of their range overlapping with sage-grouse, and 14 of those have similar habitat associations with sage-grouse. While conserving greater sage-grouse will likely have a beneficial effect on those 14 reptiles, doing so may have little effect on the other 56 species of reptiles within the ecosystem.

A more comprehensive ecosystem conservation approach is in tension with the strictures of ESA and its focus on individual species. However, to the extent that voluntary conservation efforts are increasingly focused on ecosystems and landscapes, successful efforts to conserve those biological communities on their own terms – and not through proxies such as individual indicator species – will reduce the need for the individual species that inhabit them to be listed under the ESA. Efforts in this direction can be further bolstered through a strong focus on collaborative conservation programs, including both interagency coordination to better leverage agency resources, expertise, and authorities, and also through work directly with private landowners and regulated entities.

Biodiversity and the Future

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 is a product of its time – it seeks to recover critically imperiled species, subspecies, and populations, and preserve biodiversity. Over the years it has it has proven both durable and flexible – enabling translocations, captive breeding and reintroduction, and ecosystem conservation utilizing protection of keystone or “umbrella” species. Individuals and communities have gone further, working to save landscapes and working lands’ habitat for wildlife, harmonizing human and animal needs on the same limited patches of soil, water, and air.

Despite this, in America today, as in the world as a whole, an ecological crisis is unfolding, a catastrophe of epic proportions that has gone virtually unnoticed. At least 902 species have gone extinct in the last 500 years, and these are merely the species officially declared extinct and listed as such by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The IUCN also lists 14,647 species as “endangered,” 8,404 as “critically endangered,” and 15,492 as “vulnerable.” Under the ESA, 1,839 species worldwide are listed as endangered while 468 are listed as threatened. In terms of extinctions, estimates made by scientists and statisticians are likely more accurate than the official count of species confirmed to be extinct. Estimates of extinction range widely, from tens of thousands of species to as many as 100,000 species per year. The late Dr. Edward O. Wilson estimated the rate of loss to be between 1,000 to 10,000 times that before human intervention. In many cases, we don’t even know what we’re losing.

This crisis is not just an extinction crisis, but a biodiversity crisis, in which the populations of countless species are becoming rapidly diminished, in a loss of species abundance even more stunning than the loss of species varietydue to extinction. According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), between 1970 and 2016 the planet suffered a 68% decrease in population sizes of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish. The report, WWF’s latest in a series of biennial papers, garnered global media attention. WWF concluded: “The findings are clear: Our relationship with nature is broken.”

In 2019, a paper published in the journal Science announced that North America has lost 3 billion birds since 1970. In the western United States, a study of 450 butterfly species found an average population decline of 1.6% per year, with the nation’s most iconic butterfly – the monarch – having lost 99.9% of its population in the west (and over 80% of its population in the east) since the 1980s. Between April 2020 and April 2021, U.S. beekeepers reported the loss of 45.5% of managed honey populations, raising the annual average loss since 2006 to 39.4%. Bees are essential pollinators to production of $15-18 billion worth of crops each year, harbinger of a potential crisis in America’s food security.

Horseshoe crabs being bled to produce limulus amebocyte lysate, an essential component in many pharmaceuticals. Timothy Fadek/Redux.

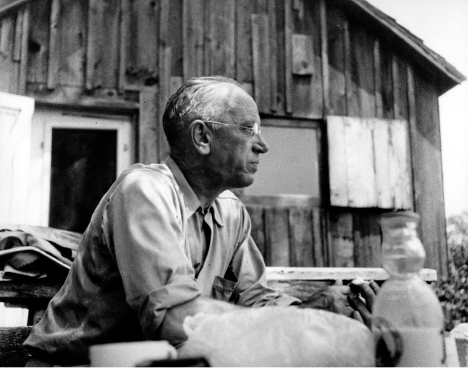

Aldo Leopold, (1887-1948). Courtesy of the Aldo Leopold Foundation and the University of Wisconsin-Madison Archives.

In the long term, biodiversity loss poses a critical danger to human health and wellbeing, and ultimately survival of the human race. 30,000 plants have edible parts, and 7,000 are regularly used as food. But just 20 species provide 90% of the world’s food and just three – wheat, maize, and rice – provide more than half. One-hundred thirty plants provide virtually all of the world’s food and feed grains for livestock. Over 40% of medications come from plants, animals, and microorganisms, but the vast majority of species with the potential to provide essential medicines have never been investigated. We do not know what incredible new medicines may be discovered in the future, or what potential medicines may be lost forever if their source species become extinct. In the words of Aldo Leopold, “to keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.”

Worldwide, the last 10,000 years have led to a one-third to one-half reduction in forests, and while the overall rate of deforestation peaked in the 1980s, deforestation continues today and is still increasing in the tropics. As many as 80% of all the Earth’s species are found in forests, especially rainforests. Other diminishing ecosystems include swamps, marshes, plains, grasslands, scrublands, shrublands, lakes, and streams. Habitat loss is a main threat for 85% of the species the IUCN classifies as threatened or endangered.

In the 1970s, when the present extent of the biodiversity crisis was scarcely imagined, Congress had the foresight to pass the ESA and stated that its purposes included to “provide a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be conserved.” But Congress chose the mechanism of regulating species on an individual basis. And partisan politics have locked the ESA into the same legislative form since 1988, now thirty-five years ago. Collaborative conservation, landscape-scale conservation, and ecosystem conservation offer innovative, conflict-reducing solutions to our present gridlock, and to the biodiversity crisis. The ESA can and will continue to be a part of our conservation solutions, especially if we can identify and implement more funding, greater flexibility, and broader partnerships. Expert recommendations for the next fifty years of the ESA can be found on this site and in The Codex of the Endangered Species Act, Volume II: The Next Fifty Years.

The Codex of the Endangered Species Act

Volume I and Volume II

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 is recognized around the world as the most important wildlife conservation law ever passed. It has led to conservation of many iconic species, including the American alligator, whooping crane, peregrine falcon, black-footed ferret, and many others. The conservation successes and challenges of the first fifty years of this law point towards future strategies for more effective and less controversial conservation under it, including legislative, regulatory, and collaborative approaches. The Codex of the Endangered Species Act explores the history of the Endangered Species Act and its success (Volume I) and possibilities for even greater achievements in the future (Volume II).

COMING SOON